Many literacy programs were not designed to effectively use multilingual students’ knowledge, skills, and strengths. This Snapshot is the third in a five-part series that provides insights from relevant research and suggests ways to engage the significant strengths that multilingual learners bring to their literacy development.

How can we strengthen and develop students’ vocabulary?

Knowing words is critical to reading comprehension. In fact, research suggests that readers need to know a vast majority of words in a text to be able to effectively comprehend it (Nation, 2013). Therefore, it is important ensure that multilingual readers have the opportunity to develop and expand their vocabularies as they engage with rigorous texts.

Build on the vocabulary students already know.

Multilingual learners come to our classrooms with a rich array of vocabulary across languages (Martinez, 2018). It is vital to see this knowledge through an asset-based lens; word knowledge in a student’s home language is rich word knowledge that can support reading development in English. As multilingual readers learn new words in English, they are also building word connections among languages they know. Additionally, research shows multilingual learners’ home language vocabularies positively impact students’ ability to use vocabulary in more sophisticated ways – like interpreting metaphors or making connections between words that represent complex ideas (Genesee et. al, 2012).

“…because deficit discourses and perspectives about bi/multilingual students often suggest that they lack words, it is important to counter these perspectives and to emphasize that lexical knowledge, or knowledge of words, is actually an area in which many of these students excel. In fact, some of these students know words in multiple languages.” Martinez, 2018

To build on what students already know

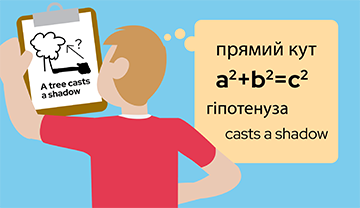

- Draw students’ attention to cognates between their home language and English. For example, the word for building is edificio in Spanish which is very similar to the word edifice in English.

- Compare and contrast the way words are used in different languages. For example

- In Chinese, the comma is stronger than it is in English.

- In English, two clauses cannot be joined with only a comma; a sentence needs a comma and a connector word like but or because.

- However, in Chinese, a comma joins independent clauses and supports cohesion in the way a conjunction might in English.

Provide opportunities to use vocabulary in a meaningful way.

Meaningful vocabulary practice happens when students are engaged in learning and can use a key word in a situation where it would be appropriate. These learning experiences may include activities where students discuss and debate ideas in a novel, or work together to solve problems while building a scientific model. Less impactful learning experiences involve introducing key words without their natural context, such as pre-teaching a list of terms, fill-in-the-blank exercises, or asking students to arbitrarily use the word in a sentence (Gibbons, 2006; Molle et al, 2021; Webb, 2019).

When students have opportunities to practice using content vocabulary in a meaningful way, it supports their ability to turn everyday words into subject-specific terms. In vocabulary teaching that is embedded in a meaningful learning experience, this happens gradually through repeated discussions of different ways to talk about and represent ideas (Molle et al., 2021). For example, in one 4th grade science class, small groups were given a model and asked to discuss what the model represents. The students grappled with different parts of the model and eventually arrived at the understanding that the model is of a lung. The students used their everyday language to grapple with their current understanding of lungs and their new expanding scientific understandings. After an engaging activity like this one, when students encounter new words in a text such as ‘diaphragm’ or ‘esophagus,’ they will have stronger connections between these new words and words they already know.

To provide students with practice using vocabulary

- Engage students in investigating words in a text: ask students to find the root of the word, related words, examples of people who would use the word and the situation in which they would use it, etc.

- Provide students with multiple exposures to words, i.e. re-reading texts or reading similar texts.

Expand word knowledge.

Knowing a word means much more than knowing a definition or even its translation. Words often have many forms, multiple meanings, as well as synonyms and antonyms (Lesaux et al, 2010). Knowing a word also includes knowing when it is socially appropriate to use the word. For example, in English, it is polite to say thank you often. However, in Gujarati, the word thank you, or ahbhar, is not used often and is reserved for formal situations or situations where you are deeply grateful. In fact, it could even sound sarcastic if you said ahbhar to a friend who brought you a cup of coffee.

A student's knowledge of a word develops over time with each repeated exposure, adding new information about what the word means and how it is used (Lesaux et al, 2010). This is especially true for words that represent complex concepts, i.e. colonialism, probability or gravity. Additionally, readers with stronger vocabularies and a more developed understanding of how words are connected are better able to learn new words through reading (Lesaux et al, 2010). Repeated exposure allows students to build connections to other words that may be in the neighborhood of words they already know. For example, while reading, a strategic reader will be able to notice that the word reaction is related to the words react and reactive and a Spanish speaker may make a connection to the cognate, reacción.

Educators can scaffold this learning by prompting students’ curiosity about words, such as ‘Let’s notice how the author uses the word react in this sentence. What are some examples of how you use the word react? Do you think we’re using the word react in the same way or a different way?’ or as a stand-alone word exploration activity, i.e. ‘I see in this sentence the author uses the word react, and in this sentence, she uses the word reaction.’ Let’s look closely at the different ways the author used the word react in the article we just read.’

“Pre-teaching vocabulary perpetuates the belief that meaning is found exclusively in words. It is not; meaning emerges as students engage with language in context.” Molle et al, 2021, p. e616, citing Gibbons, 2006

To expand students’ word knowledge

- Be curious about how students already understand the word in other contexts or other languages.

- Provide opportunities for students to share their strategies for figuring out the meaning of new words.

More Learning

Beyond Cognates: Leveraging Multilingual Capital Podcast by Ellevation

References

Freeman, D. E., & Freeman, Y. S. (2014). Essential linguistics: What teachers need to know to teach ESL, reading, spelling, grammar. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Gibbons, P. (2006). Bridging discourses in the ESL classroom: Students, teachers and researchers. Continuum

Lesaux, N. K., Kieffer, M. J., Faller, S. E., & Kelley, J. G. (2010). The effectiveness and ease of implementation of an academic vocabulary intervention for linguistically diverse students in urban middle schools. Reading Research Quarterly, 45(2), 196-228.

Martínez, R. A. (2018). Beyond the English learner label: Recognizing the richness of bi/multilingual students’ linguistic repertoires. The Reading Teacher, 71(5), 515-522

Molle, D., de Oliveira, L. C., MacDonald, R., & Bhasin, A. Leveraging incidental and intentional vocabulary learning to support multilingual students’ participation in disciplinary practices and discourses. TESOL J. 2021; 12:e616. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/10.1002/tesj.616

Nation ISP. Learning Vocabulary in Another Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2013.

Webb, S. (2019). Incidental vocabulary learning. In S. Webb (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of vocabulary studies (pp.225–239). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/97804 29291 586-15